Mitigating Postharvest Loss: Addressing Causes Rather than Symptoms

by Steve Sonka, Research Professor, ADM Institute for the Prevention of Postharvest Loss at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Recognition that reducing postharvest loss is an important opportunity to enhance global food security is not a new phenomenon. Indeed, on September 1, 1975, then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger made the following impassioned plea at the seventh special session of the UN General Assembly:

“Another priority in the poorest countries must be to reduce the tragic waste of losses after harvest from inadequate storage, transportation and pest control.”

“… we urge … a goal of cutting in half these post harvest losses by 1985.”

Kissinger’s plea had impact and on September 19, 1975, it was adopted as a resolution of the UN General Assembly, drawing global attention to the issue of postharvest loss.

Despite this significant pronouncement, postharvest loss and food waste remain at high levels. Over the last year, we’ve analyzed efforts to reduce postharvest loss in numerous global settings, primarily in developing countries. One important result of this work focuses on the comparison in the title above – causes versus symptoms. Indeed, a consistent relationship we’ve identified is that successful interventions address the complexity inherent in agricultural and food systems. Rather than supposing that one action can fix the problem, such initiatives employ a multi-faceted set of responses.

From the perspective of external observers, incidence of postharvest loss can be readily apparent. Smashed tomatoes transported in bulk, rather than in appropriate containers, can’t be sold at market rates. Rice spread on the ground to allow for sun drying is subject to consumption and spoilage by birds and other pests. Maize that is not dried properly prior to storage goes out of condition.

From the perspective of external observers, incidence of postharvest loss can be readily apparent. Smashed tomatoes transported in bulk, rather than in appropriate containers, can’t be sold at market rates. Rice spread on the ground to allow for sun drying is subject to consumption and spoilage by birds and other pests. Maize that is not dried properly prior to storage goes out of condition.

Observing such conditions, a natural response is to focus on fixing the “problem” – use better containers, don’t dry rice in the open, and employ effective conditioning practices. However, from a decision perspective, it often is important to realize that what we observe as the problem (an event) actually may be a symptom of more systematic factors. The underlying patterns and structure often systematically drive unacceptably high levels of loss.

Soybean Production in Mato Grosso, Brazil

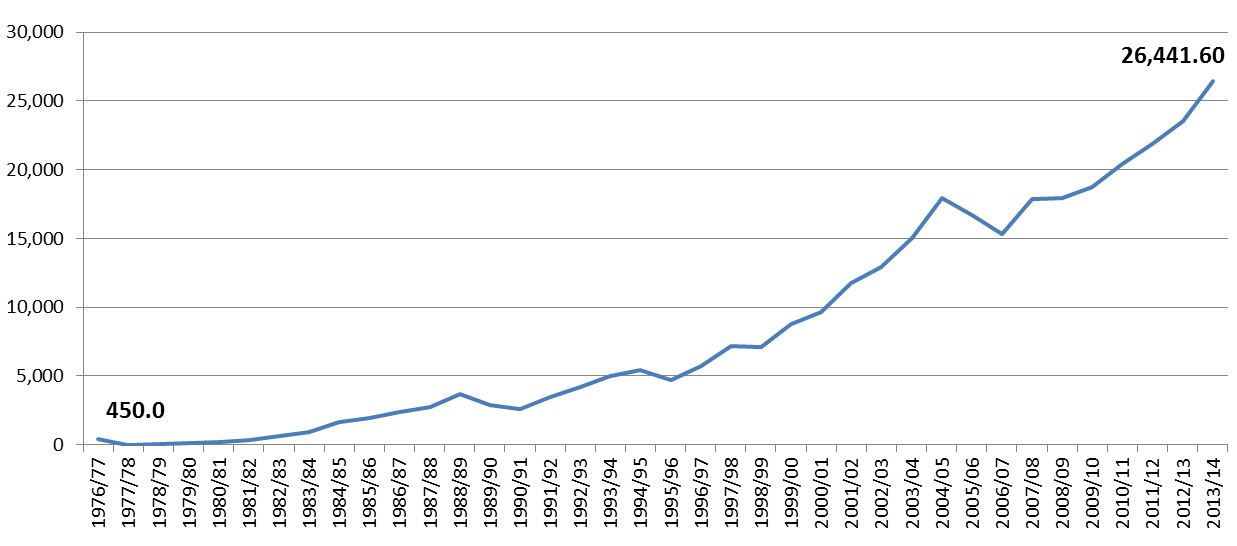

To illustrate, let’s consider a highly visible postharvest loss event in one of the most productive and progressive agricultural sectors in the world – the soybean sector in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. The increase in soybean production in this state over the last five decades has been truly amazing. In the late 1970s, the annual soybean production in Mato Grosso was less than 500 metric tons. Phenomenally, production there had increased 50-fold by the year 2013/14 [1].

Soybean production in Mato Grosso, 1976/77-2013/14 (metric tons). Source: Conab, 2014

As a visitor to Mato Grosso, one has to be impressed with the scale and sophistication of its soybean system. Large (sometimes immense) fields with uniform stands of weed-free soybeans stretch to the horizon. The prototypical harvest picture shows several modern, large-scale combines marching in unison across a soybean field which extends across the picture frame.

The “Symptom”

Yet there is another characteristic scene associated with soybean harvest there. The main roads tend to be lined with soybean seeds that have fallen from trucks during transport. As shown in the accompanying photo, soybean loss is readily apparent as the harvest progresses.

While the event – soybeans that fell from trucks – is highly visible, the underlying causes that contribute to the existence of this problem are less apparent. To appreciate some of these causes, it’s useful to consider the sector’s development experience.

The “Causes”

In the early years of soybean production in Mato Grosso, soybeans were produced as a single crop per year. Planting occurred in September/October and harvest tended to coincide with the Easter Holiday each year. Over time, however, soybean diseases developed which threatened to severely reduce yields. Responding to these challenges, soybean breeders developed less susceptible, shorter season varieties. The production season shifted with early harvest starting around Christmas and the bulk of harvest occurring in January and February.

With the shorter season, Mato Grosso farmers discovered that a second crop could be produced each year, typically maize. A key to the success of the second crop is that planting must be accomplished prior to the end of the region’s rainy season which often extends only to early March. Therefore there is considerable pressure to rapidly move the soybean crop to market. This new pattern contributes to behaviors which encourage transport losses.

A second characteristic of the structure of Mato Grosso farming is the lack of on-farm storage, at least relative to the soybean farming in the Midwestern United States. Especially given that there are long transport distances to reach international markets from Mato Grosso, a structure with more local storage would provide a means to reduce harvest time pressures and associated postharvest losses. However, until very recently, capital and financing for fixed storage facilities were limited.

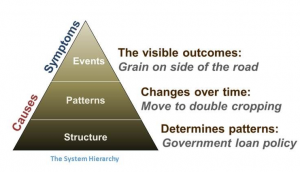

In the case of Mato Grosso, the event – grain on side of the road – is driven by the causes – the move to double cropping and lack of adequate financing. Generally, the causes which drive postharvest loss events typically are embedded in the underlying system. The immediate fix to the symptom may be a palliative, but addressing the systematic causes can prevent losses from reoccurring.

In the case of Mato Grosso, the event – grain on side of the road – is driven by the causes – the move to double cropping and lack of adequate financing. Generally, the causes which drive postharvest loss events typically are embedded in the underlying system. The immediate fix to the symptom may be a palliative, but addressing the systematic causes can prevent losses from reoccurring.

To know more about what we have learned through this project (which is supported by the Rockefeller Foundation), we invite you to watch the keynote video we recorded for a side event on “Reducing Post Harvest Loss and Food Waste” at the Alliance for a Green Revolution Forum 2014.

[1] Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento (Conab), 2014. Séries históricas (Portuguese). Retrieved from: http://www.conab.gov.br/conteudos.php?a=1252&ordem=produto&Pagina_objcmsconteudos=3#A_objcmsconteudos

This blog post is part of a series that highlights outcomes and learnings of the Global Learning Assessment project. This is the first post in this series.

The ADM Institute for the Prevention of Postharvest Loss is an international information and technology hub for evaluating, creating and disseminating economically viable technologies, practices, and systems that reduce postharvest loss in staple crops. For more information about the ADM Institute, please visit our website.

8 Comments

Thanks for this post on the Mato Grosso is interesting. It would be even more interesting if there was some diagnosis of the physical scale and loss of quality to indicate what the loss rate for the soybean crop is; whether transport losses are significant physically and financially, and whether the addition of on-farm storage through debt finance will pay the opportunity cost of the storage investment for the farmers of the region.

Thank you for the especially excellent and appropriate resource “ADM, PHL in the news” and implementing a great Development blog with Rockefeller funding,

Yes, a “cause versus symptom” is a worthy approach to the complexity inherent in agricultural and food systems.

Yes, it is easy to agree with another Rockefeller funded post by Amanda Rose “Bringing fresh solutions to the challenge of global food security” who says that “The answer lays primarily in the fact that reducing postharvest loss at scale is not about applying known technologies or techniques to a particular point in the agricultural production process.”

However, take a minute to wonder at the logistical platforms avoiding loss of “hot, take away” coffee, cell phone calls and harvest before pests ruin it.

Buying hot coffee in a “travel cup” or a number in a “mobile phone” is impressive, because the owner gets tenure, without a fixed address. An African problem solved profitably.

If collaborative problem solving networks, social innovation labs are actually leveraging best in class research, scientific expertise, technologies and other resources to address pressing challenges, why are the steps to solving moist, low calorie and dry, high calorie PHL such “a confounding paradox” (Rose, 2014)?

Orchestrate a poor (especially women) and peer review comparing how low or high calorie nutrition solves the most limiting problem first and the “readily available”, “no rocket science” (Cousins, 2013), high return “Preserving what is already grown” (Woretz, 2013) and “positive criteria reducing food loss and waste” (Lipinsky, 2014) use of Rockefeller resources is very apparent.

Even though dry high calorie mobile metal storage only moves when empty, unlike current “ceramic” and “land line” like warehouse receipt systems, mobility awards Harvest tenure to disadvantaged (women especially) dry staple grain and pulse growers at optimal points on any value chain.

At home, storage benefits the grower (especially women) when the mobility of trailers is meshed with the pest management and storage (sack or bulk) capacity of raised metal silo utility. Utility means leases or purchases scale to store in the field, facilitate Integrated pest management and later process bowls, sacks or bulk, anywhere. Utility anchors incentives for optimal production agriculture and soil management. Optimal means more carbon and water becomes organic matter (resilience) and agricultural soil eco-systems can better mitigate the impact of climate on food security.

Have any African problems been solved yet?

The reasons mobile metal storage utility is not enabling for example, more Northern Ghana daughters to graduate, rather than laboring to compensate for dry calorie Post harvest (and related input) loss might be

– politically correct warehouse receipt systems that assist West African politicians and administrators but “do not help the small holder” (World Bank and Ferris, 2013).

– described at by Aimee Rae Ocampo in “Partnerships in development: Breaking down myths.”

– awareness that Harvest tenure might cause a linear relationship between empowerment and Gender based violence in rural house holds.

“Movable storage: an innovation that merits demonstration!” (Guay, 2014) because / tonne handled, stored, monitored and marketed utility illuminates and mitigates systematic causes that can prevent Postharvest (and related input) loss from reoccurring.

References on request.

Thank you for the ADM and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne’s comment logistical platform,

William Lanier

Neveridle Farms and Consulting (Ghana)

A few decades ago Jerry la Gra and his team at the Univ of Idaho and IICA developed a loss assessment manual that identifies causes and sources of postharvest losses. I highly recommend it for anyone interested in understanding the entire commodity system (or you can call it is a value chain) and all the interacting people, regulations, infrastructure, etc that can affect food losses.

The manual is available in 3 languages. (PEF has the last of the printed/hard copies, donated by the University of Idaho) LK

Commodity Systems Assessment Manual:

English http://www.fao.org/wairdocs/x5405e/x5405e00.htm

Spanish http://www.fao.org/wairdocs/x5405s/x5405s00.htm

French http://www.fao.org/wairdocs/x5405f/x5405f00.htm

Hi Lisa! Thank you very much for sharing this helpful information!

Hello Dr Lisa K.

Nice to see you here!

I used this method for my MSc. paper developed by Jerry La Gra- the Commodity System Analysis Methodology comprises 26 components from field to consumer. Of course it requires different professionals (producers, marketers, post-harvest specialists, and others) to identify the major problems/causes and bring solutions together so that the produce is safely reach to the consumer with its maintained quality and quantity.

Thank you Lisa,

Nice resource. I eagerly spent 15 minutes skimming to look for inclusion of “Grower Peace of Mind” which Proctor identifies well in his matrix.

I am am hoping on closer study there is flexibility in both Chen’s (New Practice-Based Tool for Making Decisions on Investment in PHL Reduction) and Gra to incorporate but why have they discarded something Proctor applied very well?

Is there research I have missed that suggests “Grower Peace of Mind” lacks relevance to reducing PHL?

William

Add Comment